Making a bad hire sucks. And usually you have no one to blame but yourself. In hindsight, 99% of the time, you could have figured it out before making the offer. So why does it happen?

A lot has already been writing about how expensive a bad hire is to an organization when you add up the hard costs of salary, sunk recruiting & training costs plus the lost productivity and/or revenue. And it is easy to place the blame on needing to fill the role quickly. But when you look at the underlying causes of a bad hire, it has more to do with what you are looking for than making a hasty decision.

No one ever plans to make a bad hire. In fact, at the time of the offer most people feel like they are making a well thought-out decision. However, within a short period of time (2-6 weeks) you realize that you made a bad choice. Surprisingly, more times than not, there was a voice of dissension to making an offer to the candidate which you had ignored. Whether it was that little voice in the back of your head that you didn’t listen to, or a member of the interviewing team that raised flags that were either trivialized or not sufficiently followed-up on…now that voice you either ignored or rationalized starts telling you ‘I tried to warn you’.

When you have a bad hire, there isn’t usually a single item that is wrong with a hire unless the role is very technical and the person clearly does not have the technical chops for the job. While it typically comes down to ‘skills’ or ‘company fit’ as the cause, that is too general a classification to be very helpful. Instead, by peeling the onion on the most common ways a bad hire fails, you can then adapt your candidate selection process to address the issues at their core.

From my experience, the reasons someone does not work out falls into four buckets. In some cases, multiple buckets are at the root of the person not being right for the role. Here they are:

1. Lack of technical/functional expertise: Yes, I’ve kinda done that before, ahem.

Unless a new employee is brought in at an entry-level position and is expected to be trained for the functional role they were hired for, they are expected to have some basic technical knowledge required for the job. Whether they are a sales person who has sold before, a developer who has coded before or a designer who knows how to design, there is a repertoire the hire brings with them in their competency portfolio. But each specific role has a different emphasis on specific functional skills. For example someone who is considered a consumer marketer may know search-engine marketing and display ads, but that is very different from television advertising and market research. A Rails developer may know how to write decent code, but also needs to know how to write tests and make sure their code fits the architecture of the entire system – which can be different for every product. While some of the principles for a function are transferable, the differences and nuances of a specific role may cause an experience worker to struggle to be proficient in areas they have had limited past hands-on experience. The good news is that this could be the case of ‘right person, wrong role’ if the organization is big enough. But the key is that every functional job is different and being able to prioritize the specific traits for that job are critical to ensuring the right alignment of experience and skills.

2. Inability to develop domain expertise: The hammer who thinks everything is a nail

It is very common to hire someone with functional expertise in one industry and expect them to be able to apply them in another industry. But many times it can be a struggle to adapt to these differences. In my career, it is amazing how often I have seen someone who comes from a different industry who does not have the ability to recognize difference between markets and customers and blindly tries to re-apply practices from their previous industry to their new one. This is where an individual’s ability to take the initiative to understand the nuances between domain and industries is important. They must also have the analytical skills, patience and perseverance to figure out why something seems to work in one industry but not the other. The awareness to go back to first principles to compare and contrast company- or industry-specific models are not skills everyone has. In my experience, people who have demonstrated the ability to adapt well to a new domain typically have had at least two completely different career experiences, which made them adept at being ‘multi-lingual’. People who have had a past life in moving between two industries, working in different countries or roles in very different functions, tend to be able to mentally wear different hats. This gives them an appreciation to better diagnose a situation before prescribing a thoughtful solution instead of the generic ‘this is how we did it at X’ statement.

3. Can’t deliver results – Look at all the effort I put in!

Let’s begin with the end in mind. If someone can’t deliver results, they are a bad hire. If someone doesn’t have the drive to focus on the achieving their goals and working a project from beginning to end they aren’t going to be successful. But knowing the ‘how’ to deliver the ‘what’ is critical. At most companies, this involves teamwork, influence, tenacity, and some form or leadership or functional excellence to play nice with the rest of the organization. This is where fit, adapting to the cultural norms and using soft skills to get stuff done make a big difference. If someone doesn’t play nice with other or doesn’t have the talent to figure out how to leverage existing company systems and practices, they will struggle to be successful. It is very much like sports where an athlete’s statistics look good on paper, but when you are looking for them to perform on the field, they disappoint. Despite all the activities and energy they may (or may not) put towards the inputs, the output isn’t there. Evaluating passion, ownership and drive are not always part of candidate evaluation feedback forms, but it is an intangible worth measuring.

4. Lack of self-awareness – {silence}

If there is one trait I have seen in nearly every bad hire I have made, is that the person was mostly unaware of the cause of their ineffectiveness. While several of them knew things weren’t going great, there was a lack of inward analysis and curiosity to try and discover why. They did not have the ability to look retrospectively on themselves and reflect at what is transpiring. If they did seek guidance, they simply didn’t (or weren’t able to) apply the feedback. Instead they just keep repeating the same methods over and over and seeing the same outcomes. Not being able to self-identify the problem or apply feedback is one of the most frustrating aspects for the hiring manager, because now you have two problems to solve. The first is the competency gap between the new hire and the job and the second is expending a large amount of energy preparing and delivering the reality check to the person. This is a big time and emotional investment. Ugh. There is nothing more draining than having a conversation with someone who is oblivious to their performance.

If you’ve made a bad hire before, at least one of these items probably crossed your mind (or was pointed out to you by a hiring team interviewer) before you made the offer. It is perfectly reasonable to ignore a flag that was raised if it can be fully dissected and weighted against the role’s critical success factors. But if a debate about the qualities of candidate is identified by a single voice of dissension, you may be missing a potential bad hire’s Achilles Heel even before making the offer.

In my next post, I will discuss how to address each of these buckets/ issues during the candidate selection process so you can catch bad hires before the offer is made.

About the Author: Ray Tenenbaum is the founder of Great Hires, a recruiting technology startup offering a mobile-first Candidate Experience platform for both candidates and hiring teams. Ray has previously spent half of his career building Silicon Valley startups such as Red Answers and Adify (later sold to Cox Media); the other half of his career was spent in marketing and leadership roles at enterprise organizations including Procter & Gamble, Kraft, Booz & Co. and Intuit. Ray holds an MBA from the University of Michigan as well as a bachelor’s in chemical engineering from McGill University.

Follow Ray on Twitter @rayten or connect with him on LinkedIn.

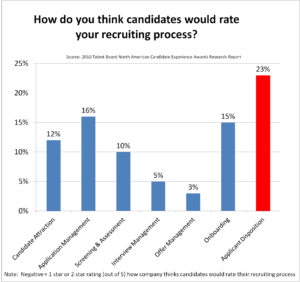

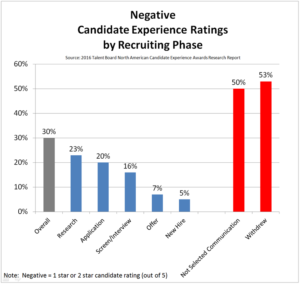

It shouldn’t be surprising that candidates get treated better as they progress down the recruiting funnel and the company gets more serious about wanting the candidate to join their organization. What is a surprise is how much the negative ratings spike after either the company or the candidate decided they aren’t right for each other. The report suggests candidates are looking for better ways to be told they aren’t moving forward when they are rejected. In addition, candidates who are withdrawing cite their time being wasted for appointments/interviews and the process taking too long as their primary reasons for taking themselves out of consideration.

It shouldn’t be surprising that candidates get treated better as they progress down the recruiting funnel and the company gets more serious about wanting the candidate to join their organization. What is a surprise is how much the negative ratings spike after either the company or the candidate decided they aren’t right for each other. The report suggests candidates are looking for better ways to be told they aren’t moving forward when they are rejected. In addition, candidates who are withdrawing cite their time being wasted for appointments/interviews and the process taking too long as their primary reasons for taking themselves out of consideration.